Wow, it has been a decade since the last comparative eraser review at pencil talk. I think the reason is that erasers have generally reached an excellent quality level. There are of course differences, but synthetic erasers from the top manufacturers in Japan or Europe are usually excellent, and the motivation to review them is diminished.

The Technik is the lightest.

The Caran d’Ache block erasers are interesting because of the shared dimensions, but differing appearances and stated functions. Caran d’Ache is also regarded as a leader in art supplies, and these products come with a reputation to uphold.

The three erasers are:

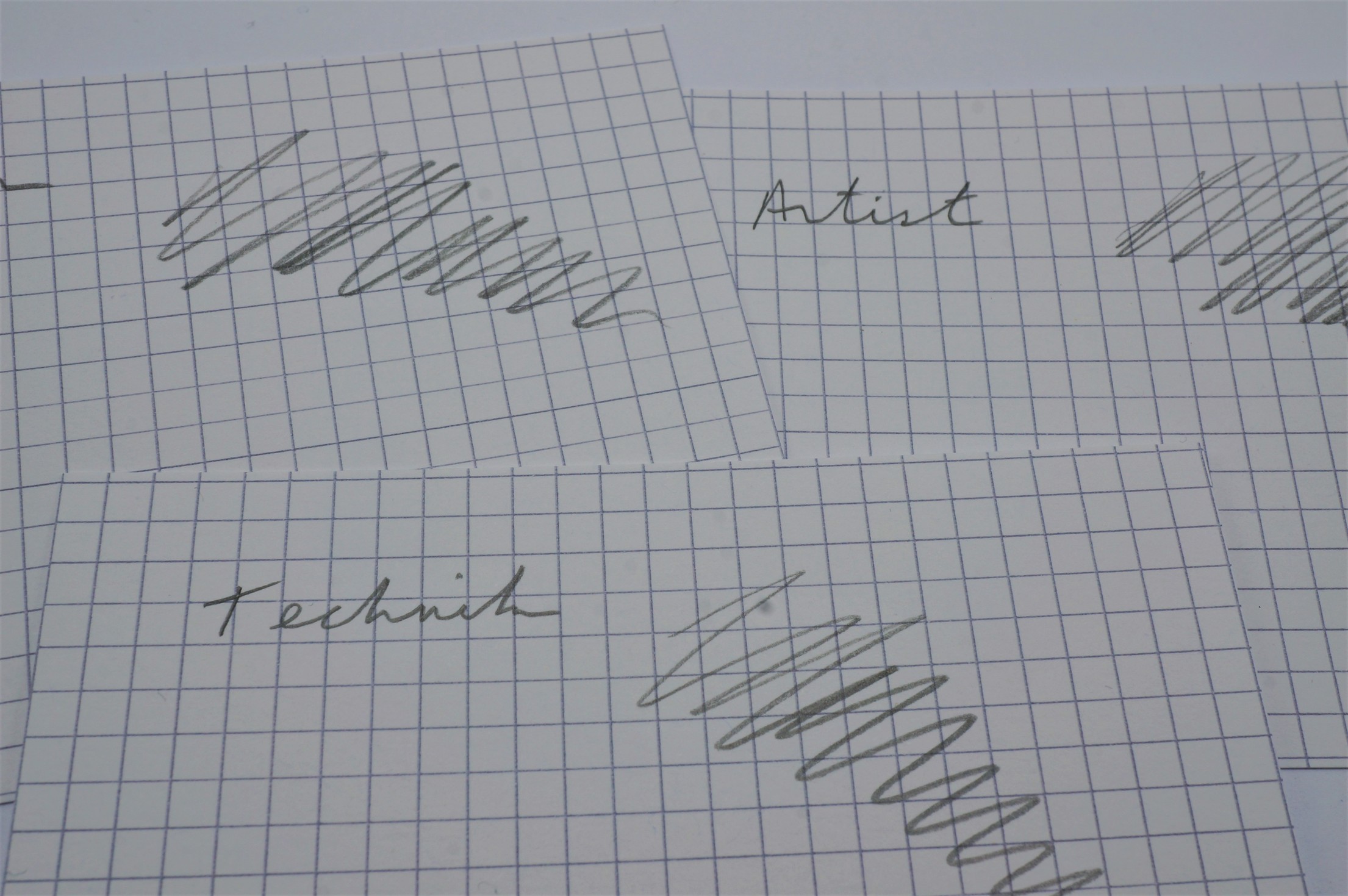

Artist 0173.420. Description: “Graphite and charcoal extra soft plastic eraser.” Green.

Design 0172.420. Description: “Graphite and colour pencil eraser.” White.

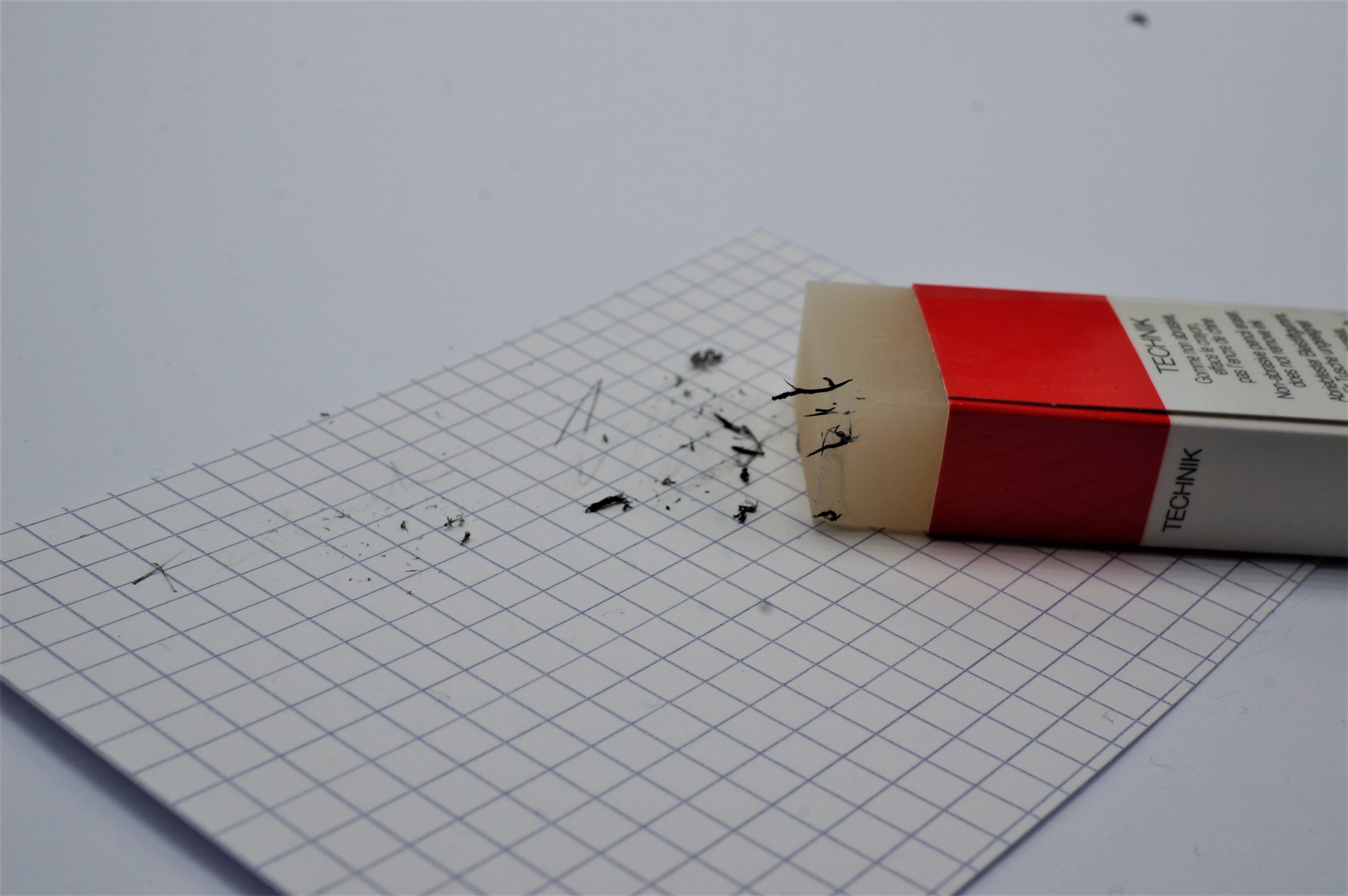

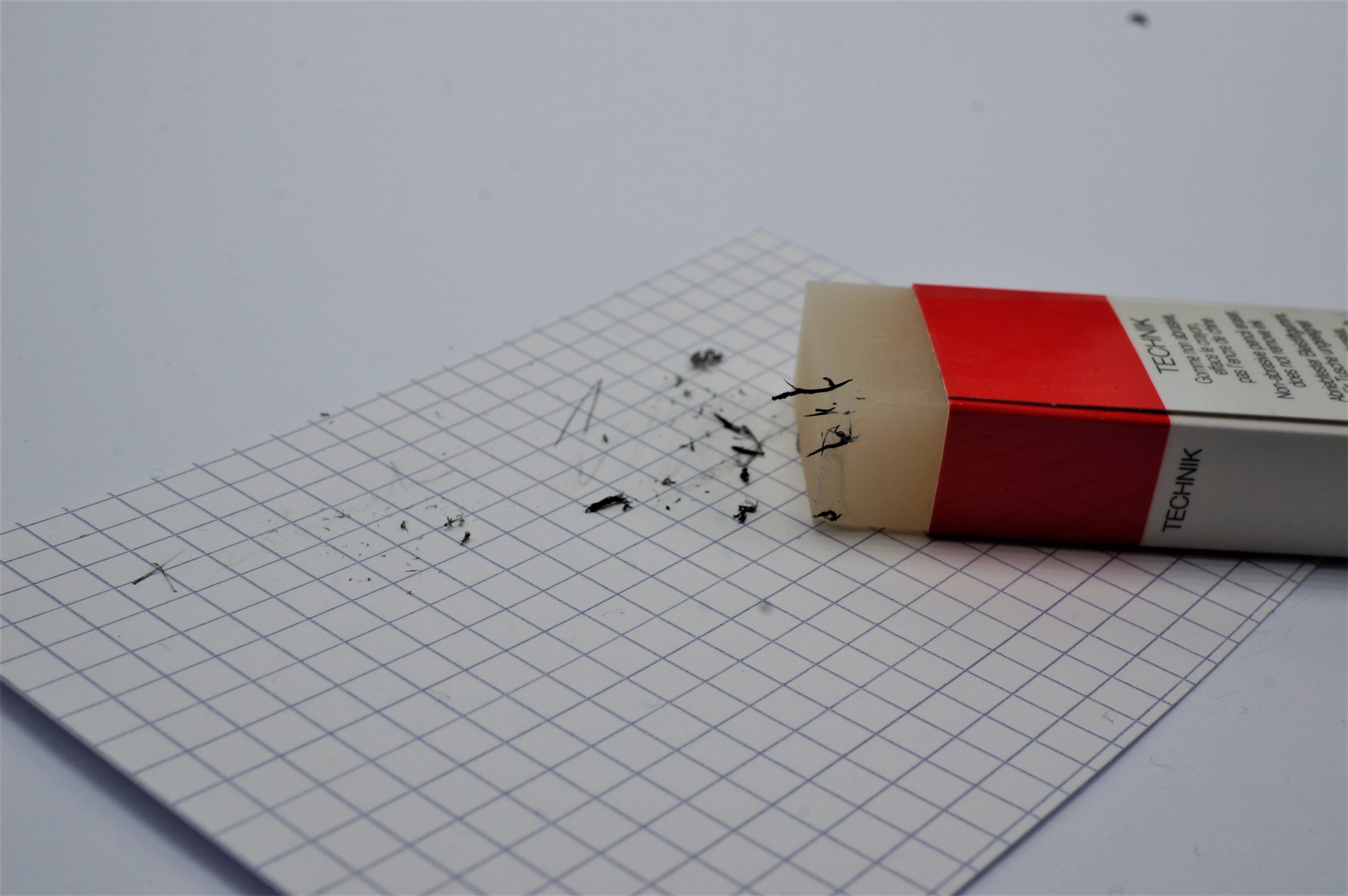

Technik 0171.420. Description: “Non-abrasive pencil eraser, does not remove ink.” Slightly translucent.

Years ago I sometimes set up very complex erasure tests, and there is indeed a complex pencil/paper/eraser/environmental factors relationship, but I wanted to keep this simpler – these erasers tested with one pencil and one test paper. I though a Caran d’Ache Swiss Wood pencil (freshly sharpened in an El Casco) would be appropriate, and decided that the Biella Index Card would be a nice companion.

All three are much harder than erasers from Tombow, Seed, etc. They also produce fine granular residue, particularly the green Artist. The Technik probably did the best job at complete erasure, and the Design is the one that most veered towards aggregation of the residue in clumps.

The erasers are good, but I don’t find them compelling when there are so many outstanding offerings available today. Of course, these are from Caran d’Ache.